Once a movie settles on its script, characters, and the behind-the-scenes crew, there’s still plenty of steps left before a project is turned into a film.

As it turns out, there’s a lot of things to do in order to make a movie. There’s cameras, music, sets, special effects, costumes, and a whole lot of other stuff, done by a whole lot of people, that has to go into piecing together the parts of a coherent narrative in a way that makes sense to an audience. Not only is this important in the screenplay and direction, it’s also the job of everyone on set from the hair and makeup department to the grip and electric department.

See, not only does a film have to make sense, it usually has to look good, too.

These elements, cinematography, costuming, special effects, etc., are the elements that can catch the attention of an audience, taking a ‘good’ film, and turning it into a ‘great’ film, thanks to the powers of movie magic.

At first, this doesn’t seem to add up to a whole lot. I mean, like I’ve been saying, movies are centered on plots and characters, and the visuals are only an added bonus.

That’s true, but here’s the thing about movies.

Movies are, basically, a story in visual form. You can have a good story and characters in a book, but you have to make up what you’re seeing in your own mind. In a film, you have to watch what someone else made up. This can be either an advantage or a disadvantage, and the difference is made entirely thanks to the individuals on the production team. These ‘trimmings’, the elements that turn a story into a film, are incredibly important, not just to the filmmakers and the process itself, but to an audience.

Even casual movie-goers can interpret what the framing of some scenes is trying to tell them, even if they don’t know that it was the cinematography that told them that. Most audience members subconsciously internalize things like thematic costume changes, or a musical cue, without necessarily figuring out what exactly was getting that point across. The point is, these ‘facets of film’ are not only for filmmakers or movie critics: The storytelling shorthand is a tool that gives the audience all of the information they need to have, without spelling it all out in dialogue.

In other words, it’s very useful.

A truly great director knows to use these aspects of ‘storytelling shorthand’ well, not simply competently. Too often, directors can decide to focus the production crew, and the movie itself, in the wrong place: the trimmings instead of the tree. It’s a common problem, one that becomes more and more obvious as the range and scope for the abilities of special effects grows. Soon enough, they’ve put the plot and characters on the backburner in order to focus on the appearance of a film, and the finished project is more concerned with being a visual masterpiece than a good, compelling story.

There’s nothing wrong with being visually appetizing, but there is something important here: a balance.

In the best examples of film, visual storytelling accentuates its story, rather than overshadows it. These facets of film are used to get the film across in the most effective way possible, focusing on what is important: the story and characters.

Such is the case with James Whale’s 1931 film, Frankenstein.

Today, we’re going to be taking a look at the storytelling devices, the facts of film used by a movie crew, to answer this question:

How does Frankenstein use its movie-making tools in order to get across the story it wants to? And does it do it well, or just competently?

Let’s take a look, starting with something that may seem kind of obvious: the camerawork. (Spoilers below!)

The camerawork in a film can sometimes be the dealbreaker, or the dealmaker, depending on how it’s used. When the cinematography is done well, it’s breathtaking, when done competently, it is adequate, but when it’s done badly, you really notice. There’s a whole lot more to camerawork than just pointing it at the action. There’s a lot to consider, like setting, lighting, character placement, colors, mood of a scene, and even mood of a character. And trust me when I say that that’s not all they have to be thinking about.

The cinematography, along with the editing of shots, is purposefully trying to get a reaction out of the audience. A good director knows how to use the camera and his crew to emphasize certain details, moods, or even subtle clues or indications of the story itself in just what the audience is looking at. The camera is not just ‘pointed at the action’, it’s used to help tell the story, while leaving a visual mark on it.

Frankenstein demonstrates this masterfully.

There are plenty of examples of striking visuals in this film, scenes like the initial pan in the graveyard, taking in the tombstones, the funeral party, and finally Henry Frankenstein and Fritz. Or the fantastic ‘raising of the monster’ scene, combining the sparking of electricity and the intense visual atmosphere to build a tension of terror, or the utterly gripping shot of Henry watching his creation’s hand move. While all of these scenes are great, unfortunately, I can’t go shot-for-shot through Frankenstein to show you all of them. (Though stay tuned for scene spotlight, a feature that’s going to do just that) What I can do is point out a few special examples.

The first one I want to bring to your attention is a weird example. It’s the scene where Elizabeth and Victor are talking about how worried they are for Henry. This doesn’t sound like it should be all that interesting, after all, we want to get to the monster, but James Whale knew where to point a camera.

Most scenes open with an establishing shot, a wide shot that lets the audience get a look at where we are so they can orient themselves and the characters in the context of the area. This scene doesn’t do that.

It opens on a series of close-ups: The framed photo of Henry, Elizabeth’s face, the door opening and Victor walking in, and only then do you get a wide shot, taking full advantage of the grand set. Until then, the audience is subconsciously working to figure out where they are, and trying to orient themselves during it. It’s a fascinating technique, one that isn’t very common, even in this movie. It’s the only time he does it.

On the other hand, something that Whale does all the time is hold the camera at a distance from the action.

See, Frankenstein was based on a book, sure, but a book that had been adapted to the stage long before movie screens. As such, early adaptations of Frankenstein tended to be, at least a little, based on the stage play. Such was the case for this film.

As such, the movie is shot, in many instances, like a stage play.

There isn’t a whole lot of camera movement in Frankenstein. The camera is usually set kind of far back from the action, letting the audience see the players move around the set, kind of like they would in a play. The camera doesn’t move with them, just sits back and lets the audience see what’s going on. Watch the “It’s Alive!” shot, or the scene where the creature stalks Elizabeth.

Now, that isn’t to say that the camera doesn’t move at all. There’s plenty of slow pans (the shot where the monster is raised through the roof) and close-ups (the first good look at the monster). But for the most part, the audience is shown what’s going on from a slight distance, from Fritz in the classroom to Frankenstein confronting his monster.

It’s an interesting way to view the action, and at first, it can perhaps seem like a bad idea on paper. After all, you want the audience in close, being there with it. But in practice, in the film itself, it works very well. The slowness of the movement, (aided with the total lack of soundtrack) adds to tension. Being able to see the whole thing builds suspense for characters as you see what they don’t.

That being said, there are plenty of interesting shots, especially within Frankenstein’s lab, that allow you to explore the space in interesting ways, making full use of the weird angles and shadows to maximize ‘scare factor’. Even the close up of the monster’s hand moving with Frankenstein reacting to it in the same shot is a masterful example of the camera in close, emphasizing the tension of the scene. Other shots, like seeing Fritz’s hanged body in the background or that iconic first shot of the monster on its feet are all master-classes in and of themselves in using a camera to convey a feeling, as well as the story, to an audience.

But there’s more to a film’s atmosphere than camerawork. There’s the soundtrack, as well.

Or, in this case, the lack thereof.

We’re used to most movies having a soundtrack, favorites coming from geniuses like John Williams, Danny Elfman, or James Horner, but Frankenstein has no music in it at all once the opening credits stop.

Music seems like a natural part of filmmaking, from the heroic opening of Superman to the shrieking strings of Psycho, even to the haunting score of The Thing. Music sets the mood, helping the audience feel what’s going on in the story. Especially in horror, where the idea is to unsettle the audience, the soundtrack seems essential, building up tension and scare-factor in a scene.

It seems odd that Frankenstein should be so totally silent.

However, it kind of works.

The silence of Frankenstein as a film works very much to the film’s advantage. You are forced to pay attention to characters and what they’re saying, true, but that’s not really a problem often faced with soundtracks. No, the benefits of the lack of music in this case are twofold, and they’re a little unusual:

1. Eerie silence works very well for this.

2. Without music cueing the audience in, it’s up to the individual viewer to determine what they think of characters.

The first point is the easiest to discuss, so let’s start there.

The only thing scarier than the creepy theme to Halloween is no theme whatsoever.

The absolute quiet in Frankenstein renders the tension harder to bear than if there had been music to cue the audience in. Hearing nothing but the thunder during the scene of the monster’s creation renders it a more vivid experience, putting the audience in the scene without background music to remind them that they’re in a movie. Even the scenes where the monster kills are more uncomfortable without music to warn us.

So yes, it’s scarier, in a way. It also forces the audience to pay more attention.

Music tells us a lot about a character or a film. It tells us that Luke Skywalker wants more, and that Darth Vader is scary. It tells us that Rocky is better for his training. It tells us that the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park are awesome.

In Frankenstein, it tells us nothing, because it’s not there at all.

The lack of musical cues for the audience forces them to pay attention and think about what is happening. Are we supposed to be scared? Sympathetic? Both? Neither? It’s hard to tell what music would play over the monster after he accidentally drowns Maria, or after Henry survives the climax at the windmill. In that, it’s up to the audience to interpret whether these things are meant to be seen as good or bad In that, somehow, a lack thereof still allows a soundtrack to do what it does best: accentuate the audience’s experience.

This ambiguity, also present in how the film is shot, allows this film to stand so firmly so many years later: it never gives you a thorough answer over what to think about what’s going on. For all its differences with the book, it does have one thing in common with it: it extends questions for you to answer, without providing much of its own. It’s on you to decide what to think.

Even though there wasn’t any music, there was a whole lot of something else: sets.

The setwork in Frankenstein is massive, hugely expansive atmospheres and locations for the audience to marvel at, and more importantly, be unsettled by. Shades of this scope appear later in things like Edward Scissorhands (albeit with a classic Tim Burton twist) and other horror-inspired films and shows, from the thunder-and-lightning surrounded tower to the interior of the lab.

James Whale shot sets in a grand way, letting the audience experience the grandiose scale of each individual location. From the huge Frankenstein mansion to the interior of the mad-scientist lab, to the cemetery, even to the burning windmill, each setting feels larger-than-life, giving the gothic set-design an even better chance to shine. The Frankenstein manor feels appropriately impressive, bright and safe, with shots that emphasize the scope of the luxury and the various rooms inside. The mill feels dangerous, dark and cramped, with too many obstacles.

But of course, the set that everyone remembers is the Frankenstein lab, and with good reason.

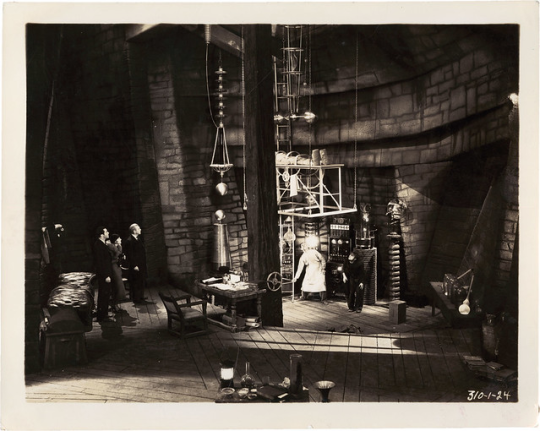

The tower, the stone walls, the electric gadgets and gizmos all going off together, the operating table, beakers galore, levers, control panels, and an open ceiling to raise the monster, now this is a mad-scientist laboratory.

Originally created in 1927 silent film Metropolis but codified forever in Frankenstein, James Whale knew how to shoot this set. Loosely based originally on the labs of Nikola Tesla, the lab of Dr. Frankenstein is so iconic that it’s been recreated (or re-used) in everything from straight horror films or loving spoofs like Young Frankenstein. Whale allows this place to feel unsettling, scary, helped enormously by Colin Clive’s crazed and uncomfortable performance as Henry Frankenstein. The lab, much like most of the sets in the film, is full of dark shadows, of stark contrasts, feeling intentionally scary.

Every set in this film is shot with plenty of shadow and darkness, allowing the audience to really feel uneasy. But the sets aren’t the only thing that are adding to the scare-factor. Also helping out drastically in these scenes is the special-effects department.

Long before the invention of CGI, monsters had to be created in the makeup chair. The original looks what’s considered the ‘classic’ monsters were created through layers of makeup and prosthetics, from Dracula’s fangs to the Wolfman’s animal face. The Frankenstein monster was no different.

The appearance of the monster could possibly be considered as the greatest special effect this film has to offer. The heavy lids, hollow features, electrodes and flat-topped head are all iconic visuals that continue into modern pop culture, and with good reason.

The effect of the original Frankenstein makeup was stunning, and instantly memorable. For a film made in 1931, the makeup on the original monster looks incredible, standing the test of time almost ninety years later. It remains a convincing effect, giving the creature a distinct, undead look that is incredibly striking.

But the visual look of the monster wouldn’t mean much of anything if it was just a makeup job. There has to be something there behind the makeup that makes it really work: the performance of the actor underneath.

Thankfully, Boris Karloff was more than up to the task.

See, no matter how good the cinematography, sets, or makeup, Frankenstein would be nothing if not for the final, essential ingredient: the performances.

And it is here that the movie goes from good to great.

As I’ve mentioned before, Frankenstein has no ‘small’ performances. Everyone in this film brings huge energy to each role, and no one more so than the monster himself, Boris Karloff.

Karloff manages an incredible range of expression through the heavy monster makeup, bringing out the monster’s innocent initial nature perfectly. He is able to portray the gambit of emotions, from fear to rage, to curiosity, to joy. It is Karloff’s performance that turns the monster into a creature that the audience sympathizes with, to the point that even when he is acting ‘monstrous’, it’s hard to forget his childlike happiness at playing with Maria. Karloff’s abilities as an actor force the audience to contend with the monster’s humanity, and his expression through the ‘dead’ makeup and heavy eyelids is as incredible as it is compelling. For one specific example, the scene where the creature is first exposed to light is a classic scene, that remains moving and powerful no matter how many times you see the film. Karloff’s performance is that of a confused creature, just learning about the world and finding it a harsh and dark place.

Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein brings manic energy to his character in the first half, and regretful sobriety in the second. He is the perfect quintessential mad scientist, howling about his accomplishments and seeing nothing wrong with stealing bodies to stitch together to create life, until he realizes his mistake. Frankenstein’s transformation and breakdown is rendered believable and interesting through Clive’s incredible performance as the regretful scientist, determined to right his wrong after the monster runs loose. His switch from the emotionally-distant scientist to a man concerned with his friends and family is dramatic but understandable, and the audience buys his uncertainty just as much as they buy his mad ambition.

Mae Clark’s showing as Elizabeth, despite not getting much in screen time or dialogue, manages to portray a woman trying to remain strong despite her fiance’s increasingly weird behavior and the undead-goings-on surrounding her wedding. She’s worried, but she’s also in love, and doesn’t want to leave Henry, despite the things he’s done.

Dwight Frye as Fritz is the quintessential Igor, the hunchback assistant that we now associate so strongly with the story. He’s a nasty being, mean-spirited and is ultimately the person most likely responsible for the creature’s bad streak of luck. A bully without scruples, Fritz helps Frankenstein assemble his equipment and parts, and eventually dies at the hands of the monster, managing to remain entirely unsympathetic the entire time, which seemed to be rather the point.

Edward Van Sloan’s portrayal is that of a perfectly ‘reasonable’ scientist, an old man accustomed to the ways of science. His concern is completely understandable, and he comes across exactly as he should: the opposite of Victor, entirely on the side of caution. Unfortunately, his caution also leads to the decision of killing the monster, but Van Sloan portrays this not so much as lack of humanity, but lack of empathy and understanding that he is also dealing with ‘humanity’. He is not a villain, but he isn’t really considering the whole picture here.

It is in these elements that Frankenstein truly becomes ‘immortal’

A film can have a great script, fantastic characters, and even great sets, cinematography and makeup, but it is in these incredible, vivid, vibrant performances that the film goes from good to great. Without the sympathetic monster, the manic mad scientist, or even the crooked (in more ways than one) lab assistant, Frankenstein as a film would be just another one of the many incarnations of the story. It is thanks to all of these facets of film that Frankenstein excels, going beyond simple ‘monster movie’ to horror classic.

Everything in this film is perfectly crafted for the specific needs of the screenplay. Every inch is designed to bring this spooky story to life, without forgoing depth of either the shadows or the characters. From the sets and the camerawork to the work of the actors themselves, everything in Frankenstein fits together perfectly, a horror classic, but also simply a film classic, a landmark that definitely deserves its place in Hollywood History as one of the greatest films of all time.

James Whale and his crew certainly knew what they were doing. Every facet of film, from the camerawork to the performances, demonstrating every mood and feeling without having to explain it. The sets and characters feel perfectly realized, gothic, creepy, and compelling, setting the mood for the thrills and chills story.

Full of scares and screams, Frankenstein’s facets of film come together to convey a great tone, characters, and story, and in the end, that’s exactly what they’re supposed to do.

Thanks so much for reading, and I hope to see you in the next article.

One thought on “Frankenstein: Facets of Film”