Frankenstein is a movie with a small cast, and huge performances.

Of the five main players, only two are at the story’s central conflict: Henry Frankenstein and the monster. Other characters, like Fritz, Elizabeth, and Dr. Waldman, are important, but not necessary to the main thrust of the story. As such, although the rest of the characters do quite a bit in terms of story-driving, in the end, the plot rests on the shoulders of the mad scientist and his creation.

This, as it turns out, is very important.

See, every film, no matter the size and scope, needs characters. More importantly, it needs good characters. A movie can have an incredible budget for amazing visual effects, a stunning score, and a thrilling plot, but it all falls flat without interesting, dynamic characters to hold your audience’s attention and make them care about what’s going on.

While horror as a genre is not especially well known for creating compelling characters (some modern iterations of horror spend more time setting up stock characters to get brutally axed), examples of truly interesting horror characters do exist, characters like Ellen Ripley, (Alien) R.J. MacReady (The Thing), Laurie Strode (Halloween) and Ash Williams (The Evil Dead). What is so important to horror as a genre is that the audience is not invested in the scares if they don’t care who it is that’s being scared.

Thankfully, Frankenstein avoids this dilemma of later horror franchises, and very intelligently focuses its scares and story on what it should be focused on: genuinely moving and dynamic characters.

And it worked out pretty well for them.

After all, there’s a reason that some of these characters are some of the most memorable in the history of film. Without any further ado, let’s take a look at the characters of Frankenstein, starting, of course, with our resident mad-scientist: Henry Frankenstein. (Spoilers below!)

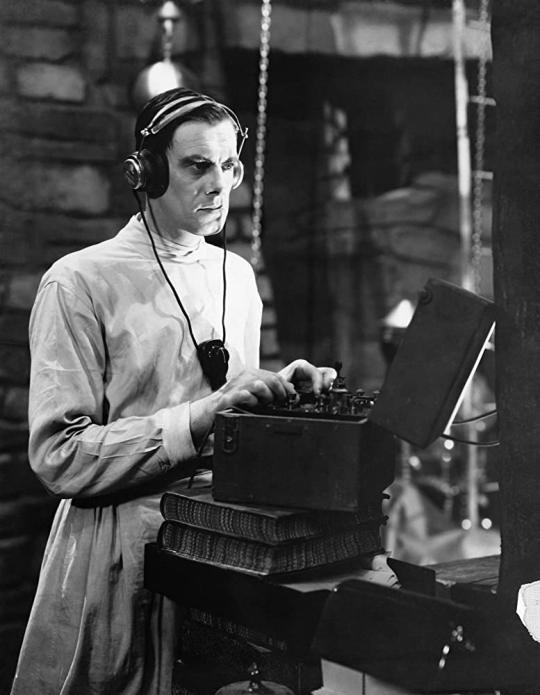

From the moment we first meet him, we know that Henry Frankenstein is Bad News. He’s the quintessential original mad-scientist, complete with howling-mad cackle and grave-robbing. He’s a man with delusions of grandeur, possessing the ambition to ‘create life’, throwing ethics out the nearest window in his single-minded pursuit of the creation of life out of death. He abandons his fiance, Elizabeth, in order to pursue said goals, and locks himself up in a creepy tower in his creepy lab with his creepy assistant, sewing together dead bodies.

Yeah, he’s not exactly a prize.

Frankenstein is not a fantastic person to have as a protagonist. He’s selfish, he’s unscrupulous, and he’s totally full of himself, convinced of his own genius, a megalomaniac in the making.

He’d be pretty awful on the whole, if it wasn’t for one thing: his change of heart.

Whether for better or for worse, (although certainly late) Henry does regret what he’s done after his creation kills Fritz. Although he didn’t seem to care much for his lab assistant before, he does feel badly, and his exhaustion and mental breakdown sends him into a downward spiral. Not only that, he remembers who he used to be.

Henry does return to Elizabeth, and realizes that he’s made a terrible mistake in cutting her out of his life for his experiments. He also realizes that he’s made a terrible mistake in conducting those experiments in the first place. Once he recuperates and gets away from his lab, the iconic ‘mad scientist’ persona melts away to a large degree, leaving a man who is determined to focus on what’s important: his wedding.

When things go wrong, again, Henry doesn’t approach the situation like a mad-scientist.

Although he doesn’t ‘fix things’, although this whole situation is his fault, and although he never truly tried to cultivate his creation once he made it, he does endeavor to save the day, to fix the situation. He goes after the monster after it attacks Elizabeth, leading a group of villagers to confront his creation, and in the end, facing him alone.

Unlike a few other examples of megalomaniac mad-scientists, Henry knows he screwed up, and deeply regrets it, actively trying to stop his creation before it does any more harm. Even though by the end, he’s not exactly ‘hero’ material, he’s a lot closer than he was at the start of the film.

Like I’ve mentioned before, Henry Frankenstein is definitely the ‘protagonist’ of the story. He grows and changes, and he is definitely at the forefront of the story, pushing events forward. Everything that happens in this story can be traced back to him, and while we may not like him, we understand him. We as viewers don’t want him to be doing what he’s doing, but we know why he’s doing it, and he presents a compelling and interesting character, if one that’s incredibly flawed.

But we love flawed heroes. That’s probably a huge reason that Henry Frankenstein remains as interesting as he is so many years later. Like I said, he’s a tragic figure, one that we relate to, and one that we want to see make it to the end.

Oddly enough, very similarly to his creation.

The Monster remains one of the most iconic movie characters, not just of horror, but of film in general, and for very good reason. He’s the antagonist of the picture, but we as an audience can’t quite see him as a villain, either. Like Henry, he’s a tragic figure, pushing the plot forward in his own way, but unlike Henry, he can’t even express his goals and desires. In fact, he can’t speak at all.

Unlike the original novel, the monster in James Whale’s film is mute, able to utter growls and noises, but not words. (Until Bride of Frankenstein.)

To some, even to characters within the film, the creature’s inability to communicate may come as confirmation to what some already suspect: that he’s a dumb beast, an animal, a monster. The characters within the film have no qualms about killing him, because to them, he isn’t human. He’s a monster.

But the audience doesn’t wholly buy that.

The saddest thing about the monster is that he’s a newborn. A baby. He’s an infant in the world, abandoned by his creator, and mistreated, tossed to humans who want to harm him. And the audience feels for him.

The creature displays more emotion than most of the other characters in the film. We as an audience know that he’s learning, that he’s trying to understand. This is never clearer than in the scene where Frankenstein first brings the monster into the light.

Once the monster first looks at the light and is first exposed to anything other than darkness, he has a reaction that the audience instantly understands: he reaches for it. He’s curious. He’s happy. He likes it.

It’s a small moment, but it speaks volumes to the audience: this is not a mindless animal. It is a child first learning about the world.

This is even more firmly established later. After the monster has killed twice, arguably in self-defense, he runs across Maria, a little girl. She doesn’t scream, doesn’t wave fire in his face, or run away. She approaches him, holds out her hand, and asks if he wants to play with her. And he does, until he gets confused, not understanding that humans aren’t terribly buoyant, and throws her in as well, leading to her accidental death.

This tells the audience even more. We see him play. The monster is learning, picking up rules. Maria throws a flower in, the monster follows. He even smiles. In this moment, this site of a tragic accident, the audience is trapped between the horror of what happens to Maria, and the investment in what’s happening with the monster.

Because we learn at that moment that the monster is not stupid.

The only reason he can’t talk is because no one has taught him how. The reason he kills is that nobody has told him why he shouldn’t. The story of the creature is a tragic one, very similarly to Frankenstein’s, as while Frankenstein becomes more of a man, the creature seemingly becomes more of a monster.

But it’s hard to blame him for it.

Like I’ve said, the fact that the creature turned out the way he did is largely Henry’s fault due to a lack of teaching on his part. Once he created this being, Henry abandoned him, and didn’t bother to teach him language, or right from wrong, or the rules of the world. He showed him light, and that, unfortunately, is all.

The creature is an antagonist, simply because he’s up against Henry, at odds with him, but we’re hard pressed to call him a villain, just as it’s difficult to call Henry a hero.

The story of the monster is all the sadder because we never get to see him live up to his potential, to grow and mature. He is destroyed, ignorant, untrained, and unloved. Despite the fact that he is an antagonist, it is very difficult to look at the creature as he dies, trapped by fire, and feel any sense of victory or justification for this creature, a monster, maybe, but not a villain.

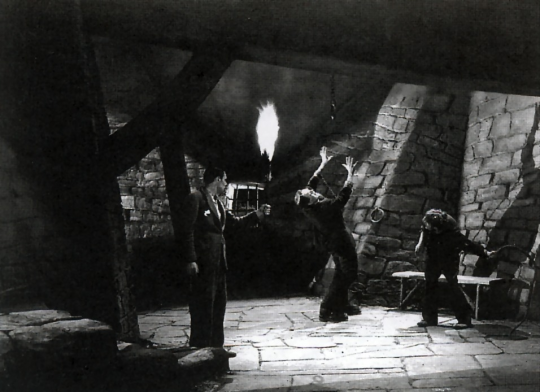

As a matter of fact, the title of ‘villain’ of this story might best be applied to the unsuspecting hunchback lab-assistant that Henry keeps around.

Fritz is a mean-spirited bully, far from the shrinking, grovelling ‘yes master’-Igor-types from later incarnations of the story. He’s an underling, an assistant, a henchman at best that Henry keeps around to do the dirty work, helping him rob graves, forcing him to climb up and cut down bodies, and go to steal brains. Henry’s a bit of a bully to him, as well, and Fritz, at the bottom of the chain, takes out his frustration and cruel tendencies on the newly-created monster.

Weirdly enough, Henry doesn’t seem to much care how he, or anyone else, treats his creation, and lets Fritz do whatever he wants for a while. He allows Fritz to watch the monster, not bothering to do it himself, and turns a blind eye to the beatings and fire.

When the creature finally lashes out and kills Fritz, the audience is hard-pressed to be sympathetic, even if Henry is. Henry even admits:

“He hated Fritz. Fritz always tormented him.”

Henry was aware of what was going on, but did nothing, and as a result, it is Fritz that, while not by any means a protagonist, or even a main antagonist, is certainly a villain. It is mostly thanks to his handiwork that the monster is the way he is: the first person to truly pay him any attention does nothing but torment him.

He’s a victim in that he dies, sure, another death chalked up to Henry’s irresponsibility and delusions of grandeur. He’s also an attacker, warping the creature for no reason, and dying the way he lived: causing misery.

Good riddance.

But he’s not the only main-character death in the story.

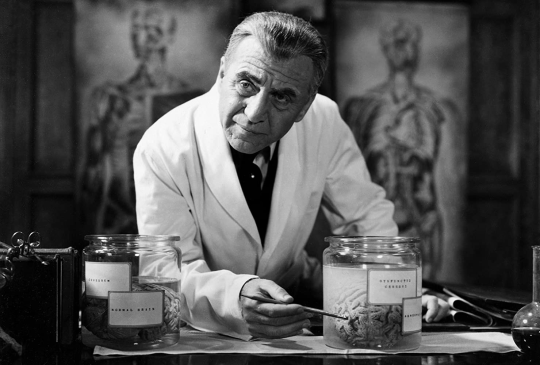

Dr. Waldman is a human voice of reason. He’s friendly, concerned, warm…and cold, at the same time.

Waldman was Henry’s mentor, his professor at medical school, who started getting nervous when Henry jumped off the deep end and started demanding corpses for his experiments. He’s a scientist, but he’s not mad. He sees the danger in Henry’s goals, and, the fountain of common sense that he is, is truly not pleased about his grave-robbing. Or his monster-making. He’s got his head on the right way, looks at the world realistically, and seems to be the moral compass between the two scientists, the right to Henry’s wrong.

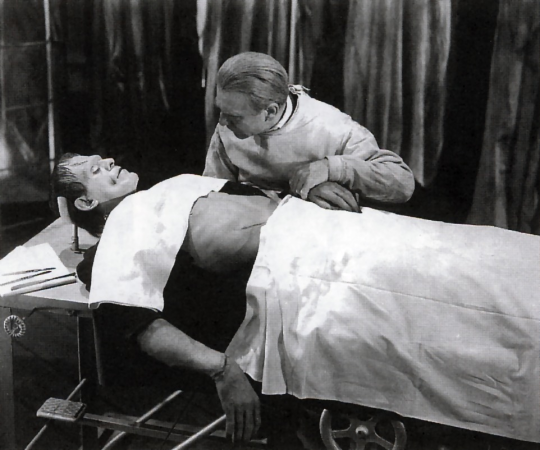

Until the creature comes to life.

After Henry’s experiment, Waldman remains a cautious and reasonable figure, at least, from the ‘human’ perspective. It is Waldman who recommends the course of action of killing the monster, ending the whole problem right away. Even Henry protests this, saying that it’s murder.

Which, it is.

After Henry has a breakdown and leaves his experiment in the hands of Waldman, his mentor tries to dissect the creature while he’s still alive, albeit possibly without realizing that he was still alive. Still, it’s interesting that not only the mad scientist, but also the careful one, via pride and miscalculation, lead the story, and the monster, into destruction.

But there is at least one character who doesn’t do anything wrong. In fact, she doesn’t really do much at all.

Elizabeth is Henry’s fiance, a kind, pretty woman who is devoted to Henry, and is quite concerned for him. Understandably, she’s a little shaken by having a fiance who reanimates the dead and ends up ruining their wedding day.

Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot else to her.

Elizabeth’s dialogue mostly consists of worrying about Frankenstein and talking about how much she wants to get married to him, taking a break to scream and faint when the monster comes after her in her room on her wedding day. She’s traditional Hollywood damsel fare of the era, you’ll find ‘Elizabeths’ in The Invisible Man, (Also directed by James Whale) and plenty of other Hollywood horror flicks of the time. Long before the tough horror-survivalists like Laurie Strode or Ellen Ripley, the Elizabeths worried about their boyfriends or fiancees, and fainted when the monster came after them.

But still, that’s being a little unfair to Elizabeth. After all, a weak woman doesn’t march up to their fiance’s creepy lab and watch them create a monster. She does go to confront Henry, attempting to do something about his problematic behavior. Unfortunately, she doesn’t get to do a whole lot else. But then again, neither do most characters.

Elizabeth actually survives the film, unlike Fritz or Waldman, and after all, it’s not really her fault that she doesn’t do a whole lot. Like I said before, the story isn’t about Elizabeth, or Waldman, or Fritz. It’s about Henry and the monster.

There are other characters, like Henry’s father (Who has little personality outside of being cantankerous), or Henry’s friend, Victor, (who has very little personality at all but who existed to take care of Elizabeth, since in an earlier script, Henry was killed at the end), or the Burgomaster (who’s not really there for long at all), but for the most part, the characters audiences remember boil down to Henry Frankenstein, the original mad scientist, and his creation.

With good reason.

Even just those two characters make Frankenstein iconic. It is these two people who are so memorable, nearly ninety years later. While not necessarily feeling ‘realistic’, (because they don’t) they are compelling, and the audience understands and feels for Henry and the monster.

The brilliance of Frankenstein is in these larger-than-life caricatures: the mad-scientist and his monster. We cannot believe that they are real, but we do get to know them and care about them. It feels bare bones, stark and open, showing the audience one man’s horrible mistake, and the tragedy that came from it, surrounding people that we like. It asks you to consider Frankenstein’s arrogance, and the impact it had on so many. It finishes with a sad ending, but a good ending, an ending with closure, and we as an audience care, not just about Frankenstein, but his monster as well. Their ending, their lives, matter to us in the way that all characters are meant to.

In short? There’s a reason Dr. Frankenstein and his monster are so beloved and so iconic years later. Their spot in Hollywood’s hall of fame and history is well-earned, and they remain legendary to this day.

Thank you guys so much for reading! If you enjoyed it, stick around for more, as we discuss Frankenstein’s place in the culture of 1931 next time! Don’t forget that the ask box is always open for questions, suggestions, discussions, or just saying hi. I hope to see you all in the next article.

One thought on “Frankenstein: The Characters”