It doesn’t seem possible that Frankenstein can be sorted into any genre except horror. A monster on a killing spree, a mad scientist in his lab, spooky shadows and an opening in a graveyard? It can’t be anything but horror, can it?

Turns out, it can.

Like we’ve discussed before, every story ever created, no matter how simple or complicated, has to fall into at least one genre. Genre is the sum of similarly themed parts that come together to give a style and theme to a story, a form of shorthand to give the audience an idea as to what kind of story they are about to see. And in almost every case, it’s never as simple as it seems.

Characters, stories, settings, and even themes often correspond to different genres As a result, it’s extremely useful as viewers to examine the categorization of films, as it not only sets up our own expectations for individual stories, it also helps us expand the boundaries of genres as their limits are tested.

Which is why Frankenstein is a bit of an odd duck.

I’ll show you what I mean.

Today, we’re going to be looking at the characteristics of the story of Frankenstein to determine what genres it is, what genres it is not, and the whys and wherefores behind them. Let’s take a look. Spoilers below!

An easy way to figure out the genre of any given film is to take a look at the setting of a story. Movies set in outer space tend to be blanketed in the genre of science fiction. Movies set in medieval times are often considered fantasy. Movies set in creepy castles or spooky swamps tend to be considered horror.

Which would seem to be the case with Frankenstein.

It seems obvious. Frankenstein, along with Dracula, The Wolf Man, The Invisible Man, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon created and codified the film genre of ‘classic horror’. These were the templates from which all future monsters would spring, werewolves, vampires, zombies and fish-creatures alike.

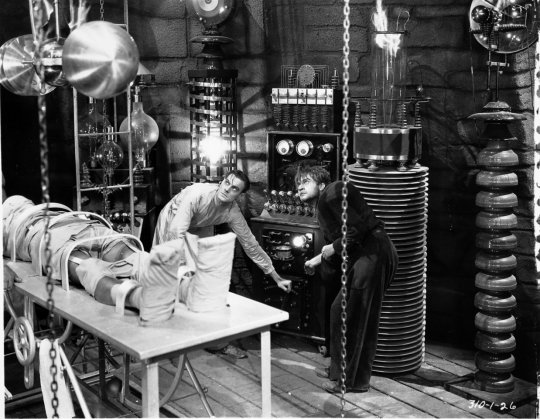

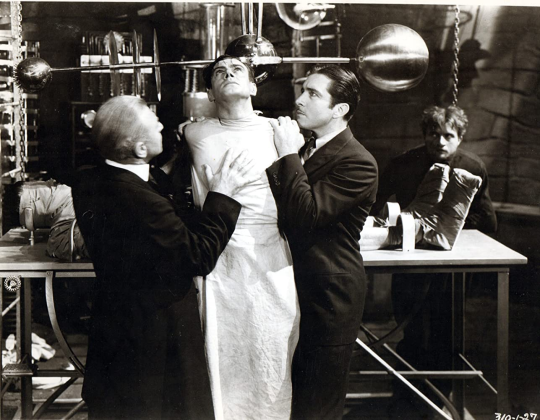

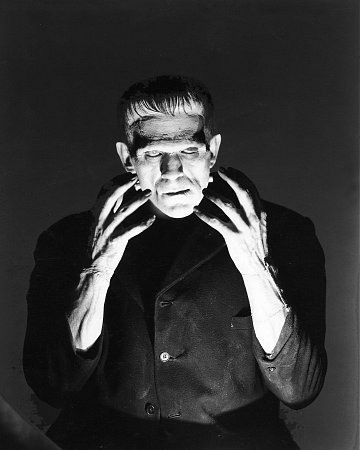

The spooky, Gothic shadows and creepy angles, the mad-scientist lab, the scenes in the graveyard, skeletons at the fringes of shots, and of course, the monster himself, would seem to speak to an incredibly obvious horror leaning. In fact, the story’s visual language was based on German Expressionism, which had been used in films like Nosferatu, a bonafide silent horror classic.

But…aren’t horror movies supposed to be scary?

There are no jump-scares in Frankenstein. Characters do not die in horrifying ways. They aren’t stalked, nor are they picked off in a way that’s traditional of horror films, and of the three characters who actually die, two were killed in what could be argued as self-defense by the monster.

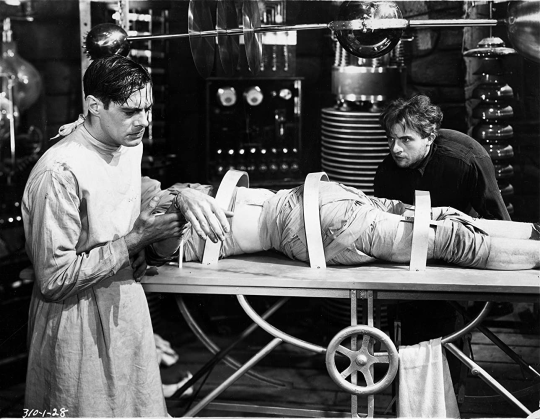

Weirdest of all, except for possibly the initial scene of his creation, up until he breaks into Elizabeth’s room, the monster is not set up as being ‘scary’. He’s set up as being sympathetic.

From the first real scene we have of the monster, where he’s lifting his hands in fascination towards light and then cowering from Fritz’s brutality, this is a creature that the audience finds themselves sorry for. This is not typical of movie monsters. There was no pity for Dracula, no concern for The Invisible Man or The Mummy. They were truly monsters, who knew what they were doing.

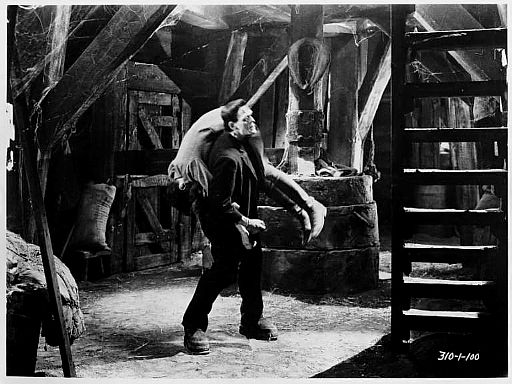

The Frankenstein monster doesn’t. For a long time, the monster reacts, rather than acts. With that knowledge…he doesn’t really come out of this, at least, the first half, looking like a monster. He’s a scared creature, mistreated into becoming a twisted version of what he could have been, a blank template upon which cruelty has been imprinted.

After the change has occurred, after the monster turns into an active character and goes after Elizabeth and attacks Henry, after so much time of the audience’s built sympathy for this creature, then we feel scared of him. We realize that he is an incredibly threatening figure, that he can be dangerous, but we never truly let go of that sympathy. At the end of the film, we don’t necessarily feel victorious that he is trapped, burning to death in that mill. We feel sorry. As much of a threat as the monster became, he didn’t start out that way. It didn’t have to end like that. But it did.

Hence my case for a rather unconventional idea.

I hypothesize that Frankenstein is a tragedy.

Like I’ve said before, this is a sad story, and I think it was that way by design. I subscribe to the theory that you can best tell the genre of a film based on what kind of characters are in it, and that works especially well for Frankenstein.

You see, as I’ve said before, there is no ‘good’ or ‘bad’ side in this film. The monster is framed as both victim and threat.

And so is Henry Frankenstein.

As an audience, we are not encouraged to wholly dislike either character. (In fact, the only character I believe we are meant to truly hate and fear is Fritz, a character who manipulates his power to inflict cruelty on the monster.) We recognize Henry’s mistakes, we realize that he’s not making the best decisions and we want him to perhaps not reanimate the dead, or maybe at least once he does, treat his new undead son with some respect, but we don’t completely hate him, even as we accept that this whole thing is basically his fault.

Henry is framed as sympathetic. We understand why he feels the way he does, even if we don’t agree with it, and we can figure out why he’s acting the way he is. He has his redeeming moments: his relationship with Elizabeth, once he stops digging up graves is genuine, and the fact that he doesn’t want the creature destroyed could point to a sign of his caring about his creation, even if he sucks at showing it. Even if we don’t relate to Henry, exactly, we understand him, and we don’t necessarily want him to die. He’s a tragic character, a figurative Icarus who aimed too highly for a mortal.

Besides, he was so delightful in that whole ‘raising the dead’ scene. I mean, that’s movie history, right there.

As for the monster?

The monster is actually the most sympathetic character in the entire cast. (Except for maybe Elizabeth.) We get to see his entire lifespan, his birth, life, and death, (Until the sequel) and it’s not a pretty picture. He’s hurt, frightened, and alone, with no-one willing to actually help him function as a being, as a person, instead of as a successful scientific experiment. Henry doesn’t seem to know what to do with him once he proved that he could create life, and as a result, the monster is left alone, with no education in how the world works. He has to figure it out on his own, and the makeshift teachers don’t really help much, either. Fritz abuses him, Dr. Waldman tries to dissect him, and Henry doesn’t pay him much mind after showing him light. Even when the monster meets Maria, he doesn’t know enough about the world to understand that his actions would kill her.

Even further supporting my theory is the ending.

The end of the story, after Henry chases his creation down and faces off with him in the mill, eventually struggling and falling while the villagers burn the mill down, is not played as a victorious climax. This is not the end of a good vs. evil struggle, there is no breath of relief that an audience feels after the defeat of Dracula, Michael Myers, or Freddy Krueger, or even Norman Bates. The ending is solemn, if not sorrowful, as the audience is left with the death of a creature who had experienced misery for the few days that he had lived.

Both protagonist and antagonist share in what is, quite simply, a tragic ending. Henry isn’t even the one to right his own wrong. The monster is slaughtered by an angry mob. Henry never reconciles his mistake. People have died, senselessly, and it could have been avoided, and not in the no-don’t-split-up-you-idiots-there’s-a-killer-in-the-woods way.

The audience is not meant to feel happy or triumphant at the end of this film, in my opinion. In my opinion, we are to mourn both Henry’s arrogance, and the monster’s demise, representative of a life wasted.

Does this mean that Frankenstein is not a horror film? Absolutely not.

Frankenstein codified almost everything we know about classic horror to this day, potentially inspiring things like the zombie horror-genre and influencing Gothic horror in general. None of this to say is that Frankenstein is not meant to be a scary movie, because, in 1931, it certainly was. People were scared, and it was definitely the filmmakers goal to do so in some scenes. The scene where the monster stalks Elizabeth in her room is definitely scary, and the dark lighting adds to the unsettling look and feel of the entire film. The scene where Frankenstein creates the monster remains a staple of best horror scenes, and has influenced countless films since then.

No, Frankenstein is definitely a horror film, make no mistake about that. It’s delightfully scary, full of creepy visuals, unsettling imagery, and a genuinely frightening core story idea: humanity being just capable enough to create life, but not capable enough to see it through competently.

But, horror is not the only genre that Frankenstein demonstrates.

Mary Shelley’s original Frankenstein novel, despite being an excellent example of horror fiction, is also considered the first example of science fiction. If you’ve been following our ‘Legacy of Science Fiction’ series, you’ve probably noticed a few of the trends that tend to go along with science fiction.

A story doesn’t need to be set in the future for it to be a science-fiction story, nor does it have to have aliens or space-ships. All it has to do is be about something just beyond our current understanding, founded in science of a sort. With that understanding, it’s easy to see how Frankenstein fits that bill.

The very creation of the monster himself is the codifier of science-fiction. Although it’s different in the original novel, the fact is, the idea of a man creating life that turns into a monster is an idea thoroughly grounded in the realm of science-fiction, a story concept rooted in the idea of science. It’s also an example of speculative fiction: bringing the audience to contend with questions such as nature vs. nurture, man’s place in creation, and the dangers of not being aware of the limits of common sense and the laws of nature.

Mary Shelley’s original novel came at a time when technology was changing much of the landscape of the world as they knew it, and it makes sense that in her story, this strange, unnatural technology would create a monster to be feared and pitied. In Frankenstein, the methods of this new generation of scientists, presenting seemingly no limits, is as horrific as the monster itself, the power that mankind can access without necessarily the wisdom to do so.

To quote Jurassic Park, the basic premise of the horror and science-fiction of this story is:

“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

And in the end, much like Jurassic Park, it works out terribly.

Like we’ve discussed in the ‘Legacy of Science Fiction’ series, Frankenstein practically invented the science-fiction theme of humanity’s creations inevitably leading to our own destruction, whether directly or indirectly. In the case of Frankenstein, it’s pretty direct. Henry’s creation turns on him, and although Henry survives, (and the monster seemingly does not) the premise is still there as a science-fiction device, twisted into a bit of a horror spin. The idea of human beings creating the things that will destroy them is legitimately frightening, especially when it’s played up as being ‘monstrous’.

But there’s a little more to Frankenstein than a tragic horror/sci-fi story. It’s also a drama.

A drama film is a serious story, one that presents us with situations that show us realistic characters struggling with themselves, others, or sometimes, nature itself. Drama usually doesn’t mix with horror, or science fiction for that matter, but it does here.

As I mentioned earlier, not only do we understand Henry and get where he’s coming from, we experience the exact same thing for the monster, if not more so. Unlike many examples of horror films, we’re half on the side of the creature, and get to know him as a character, rather than just a monster.

The conflict is simple, and fairly obvious. Henry’s created this being, and due to his own lack of care, is forced to ‘fix’ his mistake and go up against the monster himself. While the idea of the creation of life, and the character of the monster isn’t ‘realistic’ in traditional terms, the character is understandable and sympathetic to the audience. We understand him, and the conflict is made far more personal than it would be in a traditional ‘kill-em-all’ horror film.

In the end, that’s what sets Frankenstein apart.

Sure, the film is an excellent horror and science fiction film, but it’s not the scares or the sci-fi that we remember the most about this movie. It’s the heart of it, the sad, personal stakes of the movie that sticks with us as an audience, and a culture. There hasn’t really been another ‘Frankenstein’ type film, asking you to consider, not in a high-browed way, but in a simple, emotional way: who is the monster, and who is the man?

We don’t necessarily remember the ‘kills’ of this film. Maybe we forget things like Henry’s wedding, or the scenes with his father, but we do remember the monster lifting his hands up to try to touch the light, his dynamic creation, and the ending, far from a happy one.

We remember Frankenstein because, not only is it a good horror film, it’s also a good story that, unlike a lot of horror films, forces us to care, not only about the men, but the monsters as well. As long as we can still feel emotion for the ‘Other’, there will always be a place for Frankenstein, even almost ninety years later.

Thank you all so much for reading! Stay tuned for next time, when we’ll be discussing the characters of Frankenstein. I hope to see you all in the next article.

One thought on “Frankenstein: Genre and Themes”