Psycho, in many ways, turned out to be the little movie that could. When the idea for it was first pitched, nobody but Hitchcock himself thought it’d succeed.

The film was originally based on Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel with the same name, a novel based on the story of Ed Gein, a murderer and grave-robber who would go on to inspire The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Although studio executives at Paramount had already nixed the idea to do a film based on the novel, Hitchcock (shown the book by his assistant, Peggy Robertson) brought the idea to them again. Hitchcock had made Paramount a lot of money in the past, but even so, they weren’t willing to go through with such a risky endeavor. The script to Psycho had more violence, sex, and gore in it than had ever been seen in movies at the time. In other words, it was too risky.

But, obviously, that didn’t stop Hitchcock.

See, Hitchcock already had his own production studio, Shamley Productions, used for the purpose of creating his television anthology show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Hitchcock struck a deal with Paramount: he would finance the film himself, use his own production crew to make it, and then Paramount could distribute it.

Paramount agreed, though not without a lot of nervousness. (Although later, it would sell the rights to Universal)

Obviously, no longer using a big production company changed the project drastically. Hitchcock’s tendencies to work with big names (Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Grace Kelly) and use larger-than-life locations (such as in North by Northwest) obviously couldn’t be utilized to the same capacity with a smaller budget. (In a way, that worked out, since the iconic sets for Psycho are still standing, and remain a tourist attraction for the Universal backlot.)

Instead, Psycho was filmed starring mostly smaller names, except for Janet Leigh. The sets were cheap, and the overall look of the film was low-budget, resembling the exploitation films that Hitchcock had used as inspiration for the picture. In order to keep the budget under $1 million, the movie was shot in black-and-white, also serving to alleviate Hitchcock’s thought that the shower scene would be less effective in color.

But this movie couldn’t be viewed as merely a screenplay. As I mentioned earlier, this film was adapted from a novel, and that meant adapting had to be done.

Joseph Stefano was tasked with adjusting the screenplay, after the original script drug and seemed more suited for a television horror story (fitting, as the original screenwriter worked on Alfred Hitchcock Presents). Stefano made a series of changes to the script, slightly moving away from the original novel from which it was adapted. Despite changes however, the script remained remarkably faithful to the original story, but with a few major exceptions, especially where Norman Bates was concerned.

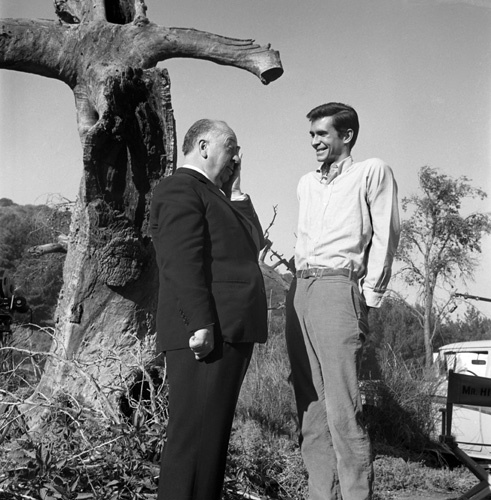

Stefano didn’t find the character of Norman Bates as written in the book wholly interesting. In the original novel, Norman is a middle-aged, overweight, overtly creepy man, making him far less sympathetic and letting the audience on nearly immediately that he is a villain. Stefano became more interested when Hitchcock suggested casting Anthony Perkins in the role, as a younger, more attractive, and more outwardly ‘normal’ Norman. (Fittingly enough Perkins lost his own father at a young age, and was raised by his mother, much like his character.) Other changes to the character included removing his alchoholism, (and the idea that the ‘Mother’ personality was brought on by a drunken stupor) interest in the occult, and pornography.

There were other changes, too. The story itself, which in the novel, opens with Norman, was switched around. In the book, Marion’s story takes up only two chapters in the story’s total 17, rather than taking up a large part of it. Hitchcock and Stefano decided it would be better if Norman was not introduced at all until nearly half an hour into the movie, making it easier for the audience to start sympathizing with him, since less was known about him.

Of course, there were plenty of more minor differences as well: Marion’s name was originally Mary, Lila and Sam had a budding romance in the novel that was omitted to make Sam look better, and there was originally no psychiatrist to explain the ending, in the novel, Sam does the exposition. Arbogast was originally murdered in the foyer, not on the stairs. The novel was also more violent than the final film: in the novel, Marion is beheaded in the shower, not stabbed.

After all these changes were made, what was left was a pretty tight script. Now all that was left was to film it.

Psycho was shot entirely at Revue Studios, on cameras specifically designed to mimic human perception, hence the point-of-view style of the film. While the entire film is covered with Hitchcock’s signature style, there are a few scenes of note that he took special care to do. (No points for guessing which ones.)

The shower scene, easily the most recognizable sequence in the film, turned out to be quite a challenge. Filming took seven days, with nearly eighty shot set-ups. The shower stall was designed with removable walls, so that cameras could be set up for every angle at any time. As for the shots focused on the shower head, an overly large showerhead was designed, allowing a camera placed very close to avoid getting wet, while getting a shot of the water flowing down. Janet Leigh, herself very exposed (with moleskin coverings barely preserving her modesty) was used for some shots, where her body double, Mari Renfro, was used for others. The shots were very difficult to achieve in such a way where the actual nudity was not captured on camera, but in the end, they were successful in portraying the idea of it, without explicit detail.

The other thrill of the film, Arbogast’s murder, was similarly difficult. For the tracking shot down the stairs, a camera was placed in a cage, hanging from the ceiling to shoot downward for the initial stabbing, primarily to conceal the identity of the murderer from the audience. For the falling-down-the-stairs shot, Martin Balsam was merely sitting still and waving his arms before a screen, displaying shots achieved by a camera on a dolly moving down the stairs.

Both of these were accompanied by that famous screeching violin sound, expertly arranged by Bernard Herrmann. Herrmann, working with a lower budget, used only strings when creating the soundtrack for the film, saying it added to the stark contrast of the black-and-white film as well as adding to the incredible tension of the scenes themselves. (Ironically, Hitchcock originally wanted no music whatsoever for the shower sequence. Herrmann went ahead and recorded the music anyway, and made movie history by creating one of the most terrifying, and iconic, musical cues in movie history.)

Finally, the film was finished. Surely with it on the way to the theaters, the movie’s journey would end, right?

Wrong.

As it turned out, the censors had a few problems with the finished project. The sexual and violent content, mild by today’s standards, was considered too high, and after efforts to get Hitchcock to cut some scenes out (to no avail, although he did allow a few minor changes for international distribution), the film was reluctantly allowed to go to theaters. (Psycho has the honor of showing the first toilet on film, which the censors also took offense to. Hitchcock got to keep the scene after arguing that it was necessary to understand where the evidence of Marion’s stay at the Bates Motel had gone.)

Once released, Hitchcock set a rather unusual rule into place: no late entries into the theaters to see Psycho. At first, theaters protested, afraid of losing business, but Hitchcock insisted, saying that if viewers attended the movie late, missing Janet Leigh entirely, they would feel cheated, and also miss out on some of the surprises. In a way, Psycho was the first mainstream anti-spoiler film. (Back then, attending a theater halfway through and waiting for the next showing was relatively common.) Theaters relented, and to their surprise, experienced lines of people, anxious to catch a viewing of Psycho from the beginning.

The rest, as they say, is history. Audiences loved the film, and, shortly thereafter, the critics did too, and, as we can see even today, the film has not lost much of its original popularity.

On September 8th, 1960, Alfred Hitchcock made movie history, pulling the rug out from under traditional storytelling and genre in general, becoming one of the most iconic and well-known films ever made, standing among the greats fifty years since its initial release.

Overall, not too shabby for a low-budget movie that studios wanted nothing to do with.

Join us next time for our final look and personal thoughts on Psycho, where we’ll be wrapping our discussion up on this movie. Don’t forget my ask box is always open for discussions, questions, suggestions, or conversations! Thank you so much for reading, and I hope to see you in the next article.

One thought on “Psycho: Facets of Filmmaking”